Understanding New York City’s Building Energy Efficiency Rating System

Image courtesy of NYC.gov

NYC’s Building Energy Efficiency Rating System Explained

The New York City Department of Buildings (NYCDOB) announced in September 2020, that it will implement a building energy efficiency rating that will require all New York City buildings 25,000 square feet or larger to post an energy-efficient letter grade sign at their entrances. The letter grade assignments are a feature of the Climate Mobilization Act, otherwise known as Local Law 97. This ambitious initiative requires buildings 25,000 square feet or larger to reduce their carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2030, and by 80 percent by 2050. The Department of Buildings will begin enforcing these carbon caps in 2024.

Who The Building Energy Efficiency Rating System Applies To

Statistically, this legislation will affect around 50,000 buildings in New York City and nearly 60 percent of the city’s building area, according to the Urban Green Council Local Law 97 summary. The summary also states that buildings are responsible for two-thirds of New York City’s annual emissions, with the other third coming primarily from on the road transportation. This has a substantial impact on energy production.

The level of transparency offered by the building energy efficiency rating will show the energy efficiency or inefficiency of a building. The New York City Council Climate Mobilization Act has identified that buildings emit different amounts of greenhouse gases, depending on their usage. The top 5 building types, greater than 50,000 square feet, are: Residential (36%), Business (26%), Institutional (12%), Hospital (7%), and Education (7%). Although in terms of average greenhouse gas emission intensity by use, for buildings greater than 25,000 square feet, hospitals emit the most greenhouse gasses per square foot. Hospitals use energy-intensive system such as ventilation, required by law for constant airflow. Coupled with other energy-intensive devices, including MRI machines and ventilators, cause an increase in emissions.

Energy Star Rating and The Building Energy Efficiency Rating System

The building energy efficiency rating is based on the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) online benchmarking tool, called the Energy Star Portfolio Manager. It is an online tool that is used to measure energy, water consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions. The tool can be used for one building or several buildings.

According to the guidelines set out by the NYC Department of Buildings at NYC.gov:

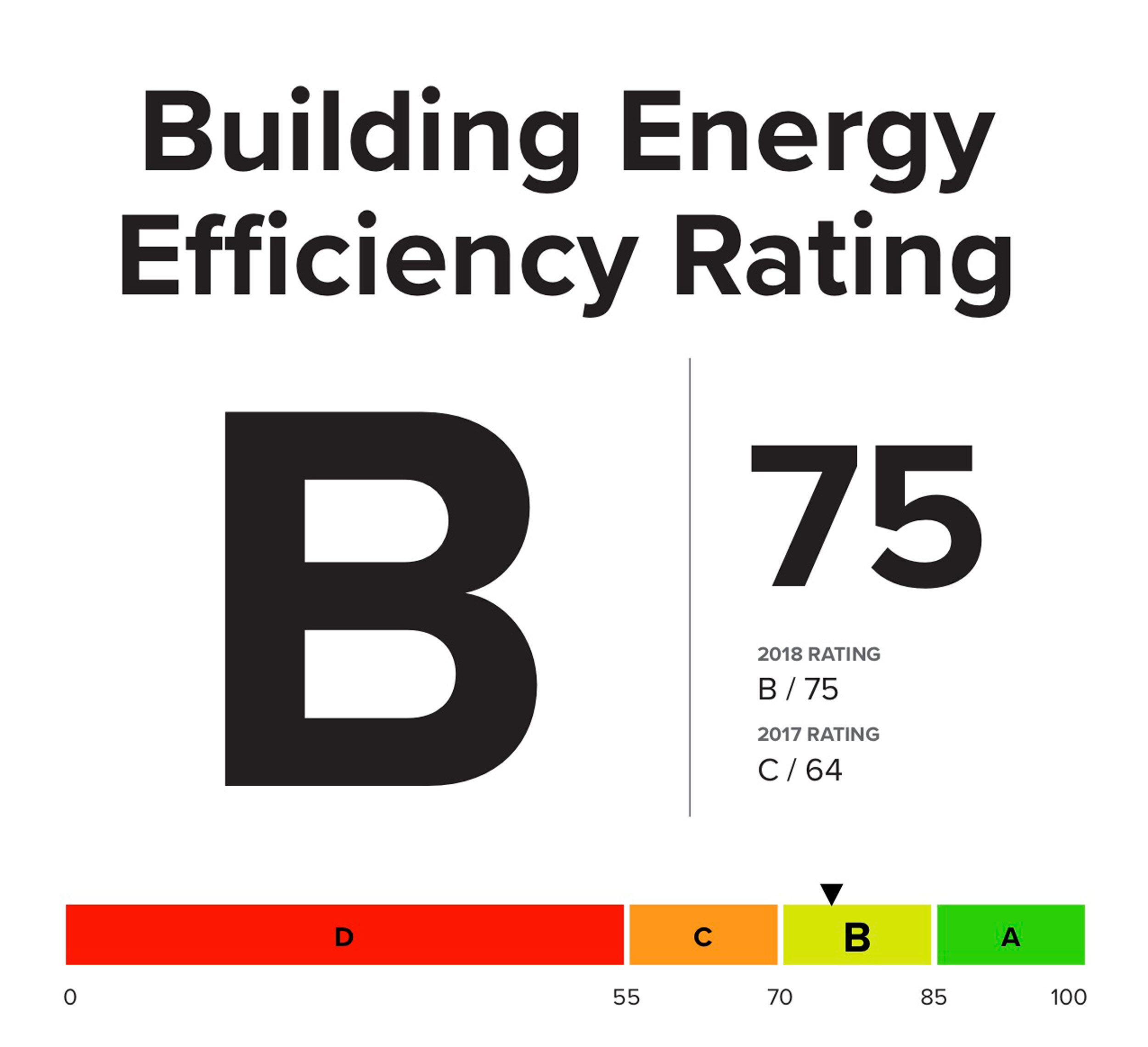

An energy efficiency score is the Energy Star Rating that a building earns using the United States Environmental Protection Agency online benchmarking tool, Energy Star Portfolio Manager, to compare building energy performance to similar buildings in similar climates. As per Local Law 95 of 2019 grades based on Energy Star energy efficiency scores will be assigned as follows:

A – score is equal to or greater than 85;

B – score is equal to or greater than 70 but less than 85;

C – score is equal to or greater than 55 but less than 70;

D – score is less than 55;

F – for buildings that did not submit required benchmarking information;

N – for buildings exempted from benchmarking or not covered by the Energy Star program.

One downside of the building energy efficiency rating is that it is primarily based on energy consumption. Consumption within different types of buildings, specifically apartments and stores, could be higher depending on activity and use of appliances, washers, dryers, electronic devices, etc. or necessity, such as refrigeration and cooling for food, etc. The EPA database estimates that 75% of an average building’s source energy occurs in private spaces. In a multi-residential setting this would be out of reach for a building manager to control or curtail. Source energy within public or amenity spaces can be controlled much easier with thermostatic and lighting adjustments based on occupancy, time of day, and seasonable conditions.

A good foundation to think about any type of interior space is in terms of cubic feet, or more simply as a series of cubic boxes that are laid out by length, width, and height. We need to heat or cool each one of these boxes. To do so we would use a source of energy, gas, oil, or electricity from a source appliance, air conditioner, hot water radiator, etc. to determine how many British Thermal Units (BTUs), a form of energy measurement, are required to heat or cool a room, considering its dimensions, its ceiling height and the approximate number of occupants. The source of energy at the site, the building, is also of consequence. If the source is solar, or wind, this could be a sustainable solution and the amount of energy loss is dramatically reduced in terms of energy transmission, or from source to site.

We have to think of the building energy efficiency rating and a path toward solutions as two-pronged: how to make adjustments, and in many cases retrofits, for a building’s energy consumption and how source energy and carbon emissions can be capped, reduced, or replaced with systems that allow NYC buildings to meet or exceed the ambitious initiatives set in place by the building energy efficiency rating.

In Part Two of this blog post, we will dig deeper to discover why certain LEED-certified buildings received a D grade under the new building energy efficiency rating energy law, the advancement of building energy modeling software and Internet of Things (IOT), and how the sun can be the ultimate energy source.

By: Tom Sembros, GKV Architects